- Wednesday, 23 April 2025

Wildfires Threat For Nepal's Ecosystems

Spring starts with flower blooms, new flushes of foliage, and captivating surroundings. But how can we forget that flower blooms have to collide with the fire blooms this season? Yes, this is the fate of spring.

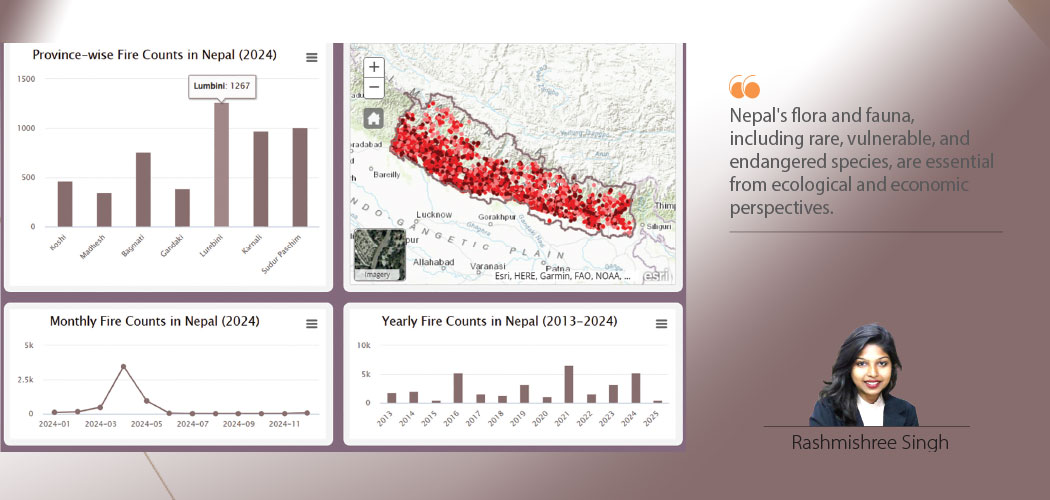

Spring, March and April in Nepal always invite the peak season of wildfires. When we look at the trendline of wildfires, their incidences are from November until June. Before the monsoon's onset, Nepal's forests are at risk. According to the Bipad Portal, forest fires only in March 2025 were 272, while those from 1 April to 6 April count as 154. In total, there were 960 forest fires in different parts of the nation.

A hot and dry winter is the ideal condition that leads to spreading wildfires, including at high altitudes. If a dry climate gets hotter and drier with a decreasing precipitation rate, it will boost fires. The alarming increase in hot days and decrease in winter and pre-monsoon precipitations fuel the fire. The escalating climate crisis intensifies an already precarious situation, fueling several environmental deteriorations.

According to ICIMOD, Nepal's forests are among the most vulnerable to the effects of climate change in the vicinity. The country’s forests cover 44.74 per cent of its land area, and the population heavily depends on these woods for its daily necessities and means of subsistence. Roughly 80 per cent of the population depends on wood for grazing, timber, and fuel. Only protected areas of Nepal cover 23.39 per cent of the total land area, which owns excellent biodiversity of different ecological regions.

The forest land area is populated for its diversity in flora and fauna. This forest land area includes protected areas, i.e., 12 national parks, one wildlife reserve, one hunting reserve, six conservation areas, 13 buffer zones, and community forests.

The main forest types in the lowlands are tropical deciduous riverine forest, tropical evergreen forest, and sal (Shorea robusta). Sal woods in eastern and central Nepal have suffered significantly from the lopping and felling of trees by the local people, yet they still create some spectacular stands of tall trees in western Nepal. One thousand eight hundred eighty-five species of angiosperms, 61 species of bryophytes, and 81 species of pteridophytes are listed from the Terai and Siwalik Hills, according to the Biodiversity Profiles Project (BPP, 1995). Of the 833 bird species in Nepal, the Biodiversity Profiles Project, 1995, reports 648 species, 111 of which are confined species, in the Terai and Siwalik Hills. Because of increased human activity in the lowlands, the wildlife of the lowlands is more endangered than that of the mid-hills or mountains. Some endangered species, like the one-horned rhinoceros, Asian elephant, and Bengal tiger, are protected in protected areas.

The mid-hills are home to 3,364 species of angiosperms, 493 species of bryophytes, 272 species of pteridophytes, and 16 species of gymnosperms, according to the Biodiversity Profiles Project, 1995. In addition, the Mid-hills are home to 691 species of birds, 110 species of animals, 76 species of fish, 29 species of amphibians, 56 species of reptiles, and 557 species of butterflies. – BPP, 1995

The Himalayan region is known for its abundance of indigenous species. They represent birch, oak, rhododendron, juniper, fir, cedar, larch, and spruce forests, making up around one-third of Nepal's total forest cover. According to the National Biodiversity Strategy, 2002, in the Everest region, on both sides of the Himalayan range, some 420 phanerogamic species have been reported over 5,000 meters in elevation. Also, mosses and lichens can be observed at 5,200 meters; blooming Stellaria decumbens cushions can be found at an elevation of about 6,100 m.

The highest wildfires were noticed in April 2003, 2005, 2009, 2010, 2012, 2016, 2010, 2012, 2016, 2019, and 2021. Approximately 90 per cent of the Terai region's woods suffered damage from fires in 1995.

More than 100 yaks were killed by fire in the surrounding areas of the Kanchenjunga National Park in eastern Nepal. Trans-Himalayan parks host rare species such as snow leopards, red pandas, and several endangered birds. A fire in 2012 destroyed almost 70 per cent of Bardiya National Park, resulting in the extinction of 60 per cent of insects, 40 per cent of small mammals, and a significant portion of birds (BBC, 3 May 2012). High-intensity, catastrophic flames destroyed 48 locations in Nepal in March 2009, including multiple national parks and conservation zones. In 2016, forest fires destroyed more than 12,000 community forests in 50 districts, resulting in the deaths of 15 individuals (ICIMOD). In 2021, the number of active fires was 6,537 (Forest Fire Detection and Monitoring System in Nepal). The condition was so miserable that the government decided to close schools across the country for four days in late March due to the soaring level of air pollution.

These fierce fires deteriorate the environment by emitting vast amounts of carbon, increasing air pollution and directly affecting humans. Several hectares of land are destroyed, degrading soil and then inducing floods and landslides. But above all, it is destroying the biodiversity of the forest ecosystem. Several rare and endangered species are under significant threat due to such harsh conditions.

Nepal's flora and fauna, including rare, vulnerable, and endangered species, are essential from ecological and economic perspectives. On the one hand, they are adding beauty to the forest ecosystem, and on the other hand, they are attracting tourists, which is of great importance to the country's treasury.

There is a hierarchy of what is to be protected in disasters. According to the hierarchy, priority is given to humans, then infrastructure, and if needed, the last priority is given to biodiversity. This is why data is available for human casualties, displaced families due to disaster, injuries in disaster, and economic loss. Still, knowing about the biodiversity loss caused by disasters like forest fires is tough.

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Nepal is portrayed as a "white spot" due to the lack of scientific data on the climate crisis. Although there are several measures to work on, government and collective effort are seen very little. There is no proper data, less action on the causes, negligence of passersby, and deliberate burning by poachers, and even if we are aware of loss and damage from wildfires, we neglect the effort that should be given from our side.

Nepal is one of the most vulnerable countries, and the climate crisis is fuelling different disastrous events, including forest fires engulfing natural wealth. Hence, it is not too late to be accountable in the context of scientific information and the protection of biodiversity. Let's hope that spring will only spread joy rather than the fierce fires that destroy wildlife.

(The author is a B.Sc. Ag. graduate from AFU Rampur.)